Socio-economic development of Arabia by the beginning of the 7th century. created the preconditions for the political unification of the country. The conquest of the Arabs led to the formation of the Arab Caliphate, which included a number of Byzantine and Iranian possessions in Western Asia and North Africa, and played a huge role in the history of the Mediterranean countries, Western and Central Asia.

1. The unification of Arabia and the beginning of the Arab conquests

Arabia by the beginning of the 7th century.

The Arab tribes that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula were divided by ethnic origin into South Arab, or Yemeni, and North Arab. By the beginning of the 7th century. most of the Arabs remained nomads (the so-called Bedouins - “steppe people”). There were much more opportunities for nomadic cattle breeding in Arabia than for agriculture, which was almost everywhere of an oasis nature. The means of production in the nomadic pastoral economy were land suitable for summer and winter pastures and livestock. The Bedouins bred mainly camels, as well as small livestock, mainly goats, less often sheep. Arab farmers grew date palms, barley, grapes and fruit trees.

The socio-economic development of different regions of Arabia was uneven. In Yemen already in the 1st millennium BC. e. A developed agricultural culture has developed, associated with the presence of abundant water resources. The last slave-owning state in Yemen was the Himyarite kingdom, which arose in the 2nd century. BC e., ceased to exist only at the end of the first quarter of the 6th century. Syrian and Greek sources note several social strata of the Yemeni population in the 6th - early 7th centuries. n. e.: noble (nobility), merchants, free farmers, free artisans, slaves. Free farmers united into communities that jointly owned canals and other irrigation structures. The sedentary nobility mostly lived in cities, but owned estates in the rural district, where there were arable lands, gardens, vineyards and date palm groves. Crops such as incense tree, aloe, and various aromatic and spicy plants were also cultivated. The cultivation of fields and gardens that belonged to the nobility, as well as the care of their livestock, was the responsibility of slaves. Slaves were also employed in irrigation work, and partly in crafts.

Among the nobility of Yemen, there were Kabirs, whose responsibilities included repairing water pipelines and dams, distributing water from irrigation canals, and organizing construction work. Some of the nobility took a wide part in trade - local, foreign and transit. Yemen had ancient trading cities - Marib, Sana'a, Nejran, Main, etc. The order in the cities, which had developed long before the 7th century, was in many ways reminiscent of the structure of the city-state (polis) of the era of classical Greece. City councils of elders (miswads) consisted of representatives of noble families.

The earlier development of Yemen compared to the rest of Arabia was partly stimulated by the intermediary role it played in the trade of Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and then (from the 2nd century AD) throughout the Mediterranean, with Ethiopia (Abyssinia) and India. In Yemen, goods brought from India by sea were loaded onto camels and continued along the caravan route to the borders of Palestine and Syria. Yemen also conducted intermediary trade with the coast of the Persian Gulf and the port of Obolla at the mouth of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Items of local origin were exported from Yemen to the Byzantine regions: frankincense, myrrh, aloe, rhubarb, cassia, etc.

In the west of Arabia, in the Hijaz region, Mecca was located - a transshipment point on the caravan route from Yemen to Syria, which flourished due to the transit trade of the Byzantine regions (Syria, Palestine and Egypt) with Yemen, and through the latter with Ethiopia and India. Mecca consisted of quarters inhabited by individual clans of the Quraysh tribe, but patriarchal-communal relations were no longer dominant here. Within the clans there were rich people - merchants-slave owners and poor people. The rich had many slaves who tended their flocks and cultivated their lands in nearby oases, or worked as artisans. Merchants were also engaged in usury, and the interest on a loan reached 100 (“dinar for dinar”). Transit caravans passed through Mecca, but Meccan merchants themselves formed caravans several times a year that went to Palestine and Syria.

The most popular local goods transported by these caravans were leather, raisins from the Taif oasis, valued far beyond the borders of Arabia, dates, gold sand and silver bullion from the mines of Arabia, Yemeni incense, medicinal plants (rhubarb, etc.). Cinnamon, spices and aromatic substances, Chinese silks came as transit items from India, and gold, ivory and slaves came from Africa. From Syria, Meccan merchants exported Byzantine textiles, glassware, metal products, including weapons, as well as grain and vegetable oil to Arabia.

In the center of Mecca, on the square, there was a cubic-shaped temple - the Kaaba (“cube”). The Meccans revered a fetish - a “black stone” (meteorite), which was inserted into the wall of the Kaaba. The Kaaba also contained images of deities of many Arab tribes. The Kaaba was the subject of veneration and pilgrimage for the population of a large part of Arabia. During the pilgrimage, the territory of Mecca and its environs was considered reserved and sacred; quarrels between clans and armed clashes were prohibited there by custom. The pilgrimage coincided with a large fair that took place annually in the vicinity of Mecca during the winter months. Near the Kaaba there was a square where there was a house in which the elders of the Qureish tribe conferred. The activities of the council of elders were determined by unwritten ancient customs.

The population of another large city in Arabia - Medina, known before the rise of Islam under the name Yathrib ( The word "medinah" means "city" in Arabic. Yathrib (Iatrippa) began to be called Medina when it became the center of the political unification of Arabia.), consisted of three “Jewish” tribes (i.e., Arab tribes who professed Judaism) and two pagan Arab tribes - Aus and Khazraj. Medina was the center of an agricultural oasis, in which a number of merchants and artisans also lived.

The social history of the Arabs before the introduction of Islam is still little studied. The process of decomposition of the primitive communal system in North Arab society is far from being clarified in detail. Solving the problem of the social development of Arabia by the beginning of the 7th century. complicated by the lack of information in the sources. On the issue of the formation of a class society here, there are two main concepts among Soviet scientists.

According to the first concept, shared by the authors of this chapter, along with the already existing slave society in Yemen, in the 6th - early 7th centuries. The formation of the slave-owning system was intensively taking place in the areas of Mecca and Medina. Throughout the rest of Arabia, the process of decomposition of the primitive communal system proceeded much more slowly. But even here, tribal nobility had already emerged, the rich, the owners of cultivated lands, large herds and slaves, who often took part in the caravan trade. Individual representatives of the nobility tried to appropriate communal pastures. Poor people also appeared, deprived of the means of production.

According to the concept outlined, the beginnings of slave relations arose in most of Arabia, but by the beginning of the 7th century. the slave system had not yet developed into the dominant mode of production (as happened earlier in Yemen and as happened by the beginning of the 7th century in Mecca and Medina). Later, after the extensive conquests of the 7th century, Arabia and especially the Arabs who moved beyond its borders were drawn into the general process of feudalization, which was already taking place in the former Byzantine provinces - in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, as well as in the countries of Transcaucasia, in Iran and Central Asia. Thus, according to this concept, the process of feudalization of Arab society dates back to the period that began after the great conquests of the first half of the 7th century, while slavery was then preserved among the Arabs only as a way of life.

According to the second concept, the slave society of Yemen already in the 6th century. was going through a crisis. In the central and northern regions of Arabia, where the primitive communal system was rapidly decomposing, early feudal relations began to take shape, which became dominant even before the great conquests of the 7th century. The Arab conquests only opened the way for more rapid development of feudal relations and the destruction of previous remnants of the primitive communal and slave system.

In any case, by the beginning of the 7th century. In the central and northern regions of Arabia, the process of decomposition of the patriarchal system was already taking place, although the connection between the Arab and his clan and tribe remained quite strong. Each Arab had to sacrifice his life for his clan, and the entire clan was obliged to provide protection to any relative. If one of the relatives was killed, the entire clan fell under the obligation of blood feud against the murderer's clan until he offered compensation. The process of the Bedouins' transition to sedentary life was hampered by the lack of suitable land for cultivation.

Arabs outside the Arabian Peninsula

Even before our era, certain groups of Arabs moved outside the Arabian Peninsula. On the border of Palestine and the Syrian Desert (in Transjordan) by the end of the 5th century. The Arab kingdom of the Ghassanids was formed, which was in vassal dependence on Byzantium. Many Arabs moved to Palestine and Syria, partially settling here; There, even under Byzantine rule, the Arab ethnic element was significant.

On the border of Mesopotamia and the Syrian Desert by the 4th century. An Arab kingdom emerged led by the Lakhmi tribe and the Lakhmid dynasty, which existed as a vassal of Sasanian Iran until the beginning of the 7th century. The question of the social structure of this kingdom (as well as the Ghassanid kingdom) has not yet been clarified. The Iranian government, fearing the growth of the military power of the Lakhmid kingdom, destroyed it in 602. But as a result, the western border of Iran was open, and Arabian Bedouins began to invade Mesopotamia.

In Mesopotamia itself, Arab settlers also appeared before our era. They were also in Egypt: already in the 1st century. BC e. the city of Copt in Upper Egypt was half inhabited by Arabs. The presence of the Arab ethnic element in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia long before the 7th century. facilitated the Arabization of these countries after their conquest by the Arabs.

Arab culture by the beginning of the 7th century.

In the VI - early VII centuries. the tribes of Northern Arabia spoke different dialects of the North Arabic language. In Yemen, Hadhramaut and Mahra, the South Arabic language was spoken. Both related Arabic languages belonged to the Semitic language system. The oldest inscriptions in the South Arabic language, in a special (so-called Sabaean) alphabet, date back to 800 BC. e. Since then, writing in the South Arabic language has continuously developed until the 6th century. n. e. But since Yemen from the middle of the 6th century. experienced decline, and Mecca developed intensively, the literary Arabic language of the Middle Ages later developed on the basis of North Arabic, not South Arabic.

The northern Arabs, who moved beyond the Arabian Peninsula, for a long time used as a written language one of the Semitic languages - Aramaic, related to Arabic. The earliest known North Arabic inscription in the Arabic alphabet is dated 328 AD. e. (inscription at Nemar in the Hauran Mountains in Syria). A few North Arabic inscriptions from the 5th-6th centuries have also been preserved. AD There was a rich poetry in the North Arabic language. It was oral, and only later (in the 8th-9th centuries) were its works recorded and edited.

Oral poetry was spread by rhapsodist storytellers who memorized poems. Among the North Arab poets of the 6th-7th centuries, the authors of the so-called muallaq (“strung poems”, i.e. poems), the largest are recognized as Imru-l-Qais, considered the creator of the rules of Arabic metrics; Antara - former slave; Nabiga is a judge of poetry competitions at fairs, etc. In their poems they sang courage, loyalty, friendship and love.

Religion

Pre-Islamic Arab religion was expressed in the cult of nature, in particular, in the veneration of common astral (star) gods and gods of individual tribes, in the cult of rocks and springs. In Mecca, as in the rest of Arabia, female astral deities called Lat, Uzza and Manat were especially revered. Crudely made images of deities were revered (cattle were sacrificed to them) and sanctuaries, especially the Kaaba temple in Mecca, which was a kind of pantheon of gods revered by various tribes. There was also an idea of a supreme deity, who was called Allah (Arabic al-ilah, Syriac alakha - “god”).

The decomposition of the primitive communal system and the process of class formation led to the decline of the old religious ideology. Arab trade relations with neighboring countries contributed to the penetration of Christianity into Arabia. (from Syria and Ethiopia, where Christianity established itself already in the 4th century) and Judaism. Christianity was first adopted by the Ghassanian Arabs. In the VI century. In Arabia, the doctrine of the Hanifs developed, who recognized one god and borrowed from Christianity and Judaism some beliefs common to these two religions.

Social and economic crisis in Arabia

From the 6th century not only Yemen, but also Western Arabia became the object of struggle between Byzantium and Sasanian Iran. The goal of the struggle of these empires was to seize the caravan routes from the Mediterranean countries to India and China, in particular the route from Yemen through the Hijaz to Syria. Both Byzantium and Iran tried to create a support for themselves in Yemen, using the local nobility, among whom by the beginning of the 6th century. two political groups appeared - pro-Byzantine and pro-Iranian. The struggle of these groups took place under the ideological shell of religion: Christian merchants acted as supporters of Byzantium, Jewish merchants sought an alliance with Iran.

The religious struggle in Yemen gave Byzantium a pretext to interfere in its internal affairs. Byzantium turned to Ethiopia, which was in a political union with it, for assistance. Ethiopia, whose army had previously invaded Yemen and at one time even subjugated it to the rule of the Ethiopian king (in the third quarter of the 4th century), undertook a military campaign in Yemen, which ended with the establishment of Ethiopian rule in it (525). The Ethiopian army under the command of Abraha, the governor of Yemen, launched a campaign against Mecca. However, due to a smallpox epidemic that broke out in the army, the campaign ended in failure. An attempt by Byzantium to establish its dominance in Western Arabia with the help of the Ethiopians caused a Persian naval expedition to Yemen. The Ethiopians were expelled from Yemen, and after some time Iranian rule was established there (572-628). The Sasanian authorities tried to direct the transit of Indian goods to Byzantium only through Iran and not to allow transit through Yemen, which as a result fell into decay. Irrigation systems failed one after another and cities declined.

The shift in trade routes from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf had a heavy impact on the Arabian economy. Mecca's trade was also disrupted. Many tribes that previously benefited from the caravan trade by providing camel drivers and guards for the caravans are now impoverished. The Meccan nobility, forced to curtail their trade operations, turned intensively to usury, and many impoverished tribes found themselves in debt to the Meccan rich.

The increasingly deepening and aggravated contradictions between the nobility and ordinary members of the tribes, on the one hand, and between slave owners and slaves, led to a socio-economic crisis in Arabia. In search of a way out of this crisis, among the Arab nobility, in particular among the Meccan nobility, there was a desire for wars of conquest, which could open up wide opportunities for enrichment by seizing new lands, slaves and other spoils of war. All this created the prerequisites in Arabia for the formation of a state on the scale of the entire Arabian Peninsula.

The emergence of Islam

The emergence of new social relations gave rise to a new ideology in the form of a new religion - Islam. Islam (literally “submission”), or otherwise Islam, was formed from the combination of elements of Judaism, Christianity, the teachings of the Hanifs and ritual remnants of the Old Arab pre-Muslim cults of nature. The founder of Islam was the Meccan merchant Muhammad, from the Hashemite clan who belonged to the Quraysh tribe. The name of Muhammad, whom Muslims regard as a prophet and “messenger of God” on earth, was later surrounded by all sorts of legends.

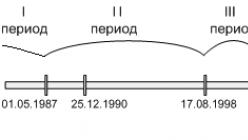

In Mecca, the Islamic preaching of strict monotheism and the fight against idolatry initially found very few followers. The Meccan nobility, led by Abu Sufyan, feared that this sermon would lead to the fall of the cult of the Kaaba sanctuary with its deities, and the possession of the Kaaba greatly strengthened the political influence and trade ties of Mecca with the Arab tribes. Therefore, the followers of the new religion were persecuted. This forced them, led by Muhammad, to move to Medina in 622. The beginning of the year in which this migration took place (Hijra) was later taken as the starting date of the new Muslim calendar based on lunar years. A Muslim community emerged in Medina, the main leaders of which were, together with Muhammad, the merchants Abu Bekr and Omar.

Muslims were called to Medina by the top of the Arab tribes of Aus and Khazraj, who hated the rich Meccan nobility, to whom many Medinas were in debt. Muslims who moved from Mecca to Medina received the name Muhajirs (migrants), which later became honorary, and the inhabitants of Medina who converted to Islam, partly from among Christian sectarians, received the name Ansars (helpers). Subsequently, the Muhajirs, Ansars and their descendants, together with the descendants of the prophet himself, formed the privileged elite of the Muslim community. Having established themselves in Medina, the Muhajirs, together with the Aus and Khazraj tribes, began an armed struggle against Mecca, attacking Meccan caravans with goods. During this struggle, many tribes of Arabia, hostile to Meccan moneylenders and merchants, entered into an alliance with the Muslims.

Prerequisites for the formation of the Arab state

The main prerequisite for the political unification of Arabia was the process of formation of classes and the growth of social contradictions within the tribes. Islam, with its strict monotheism and preaching of the “brotherhood” of all Muslims, regardless of tribal division, turned out to be a very suitable ideological tool for the unification of Arabia. Therefore, Islam quickly grew into a political force: the Muslim community became the core of the political unification of Arabia. But contradictions immediately emerged within the Muslim community itself. The mass of farmers and nomads perceived the doctrine of the “brotherhood” of all Muslims as a program for establishing social equality and demanded a campaign against Mecca, which was hated by the social lower classes, who considered it a nest of moneylenders and traders. The noble elite of the Muslim community, on the contrary, sought a compromise with the Meccan rich merchants.

Meanwhile, the Meccan nobility little by little changed its attitude towards Muslims, seeing that the political unification of Arabia that was taking shape under their leadership could be used in the interests of Mecca. Secret negotiations began between Muslim leaders and the head of the Meccan Quraysh, the richest slave owner and merchant Abu Sufyan from the Umayya clan. Finally, an agreement was reached (630) by which the Meccans recognized Muhammad as the prophet and political head of Arabia and agreed to convert to Islam. At the same time, the former Quraish elite retained its influence. The Kaaba was converted into the main Muslim temple and cleansed of idols of tribal deities. However, the main shrine - the “black stone”, declared a “gift of God” brought to earth by the Archangel Gabriel, was abandoned. Thus, Mecca continued to be a place of pilgrimage, while maintaining its economic importance. By the end of 630, a significant part of Arabia recognized the authority of Muhammad.

This marked the beginning of the Arab state, in which the ruling elite became the slave owners of Mecca and Medina, the “companions of the prophet,” as well as the nobility of the Arab tribes that converted to Islam. Some prerequisites have emerged for the future unification of settled and nomadic Arab tribes into a single nation: from the 7th century. The Arabs - nomadic and sedentary - had a single territory and a single Arabic language was emerging.

Foundations of the ideology of early Islam

Islam assigned five duties to Muslim believers (“the five pillars of Islam”): confession of the dogma of monotheism and recognition of the prophetic mission of Muhammad, expressed in the formula “there is no deity but God (Allah), and Muhammad is the messenger of God” ( In addition to Muhammad, Islam recognized other prophets, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus Christ.), daily prayers according to the established ritual, deduction of zakat (collection of 1/40 of the income from real estate, herds and trade profits) formally in favor of the poor, but in fact at the disposal of the Arab-Muslim state, fasting in the month of Ramadan and pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj), obligatory, however, only for those who were able to perform it. The teachings of Islam about angels, about the Last Judgment, about reward after death for good and evil deeds, about the devil and hell were the same as those of Christians. In the Muslim paradise, believers were promised all kinds of pleasures.

Islam prescribed Muslims to participate in a holy war (jihad) against the “infidels.” The doctrine of the war for faith and the saving significance of participation in it for the souls of believers developed gradually in the process of conquest. Religious tolerance was allowed towards Jews and Christians (and later towards Zoroastrians), however, on the condition that they submit, become subjects of the Muslim (i.e. Arab) state and pay the taxes established for them.

The holy book of Muslims - the Koran ("Reading"), according to the teachings of Islam, existed from eternity and was communicated by God to Muhammad as a revelation. Muhammad's speeches, which he presented as “revelations from God,” were recorded, according to legend, by his followers. These records were undoubtedly further processed. The Koran also includes many biblical stories. The Koran was collected into a single book, edited and divided into 114 chapters (surahs) after the death of Muhammad, under Caliph Osman (644-656). The influence of Meccan slave owners and merchants was reflected in both the language and ideas of the Koran. The words “measuring”, “credit”, “debt”, “interest” and the like appear more than once in the Koran. It justifies the institution of slavery. Basically, the ideology of the Koran is directed against the social institutions of the primitive communal system - inter-tribal struggle, blood feud, etc., as well as against polytheism and idolatry.

There is a special chapter in the Koran, “Booty,” which stimulated the Arab warrior’s desire to go on a campaign: 1/5 of the spoils of war was to go to the prophet, his family, widows and orphans, and 4/5 was allocated to the army at the rate of one share to the foot soldier and three shares to the horseman. War booty consisted of gold, silver, captive slaves, all movable property and livestock. The conquered lands were not subject to division and had to come into the possession of the Muslim community. Islam promised heavenly bliss to those killed in the war - “martyrs for the faith”. It was believed that only people of other faiths could be converted into slavery. However, the adoption of Islam by people who had previously been enslaved did not free them or their descendants from slavery. Children of masters from slaves, recognized by their fathers, were considered free. Islam allowed a Muslim to have up to 4 legal wives and as many concubine slaves at the same time.

For early Islam there was no difference between clergy and laity, between the Muslim community and the state organization, between religion and law. Formed gradually between the 7th and 9th centuries. Muslim law was originally based on the Koran. To this main source of law from the end of the 7th century. another one also joined - a legend (sunnah), which consisted of hadiths, i.e. stories from the life of Muhammad. Many of these hadiths were composed among the “companions of the prophet” - the Muhajirs and Ansars, as well as their students. As Arab society developed and its life became more and more complex, it became clear that the Koran and hadith did not answer many questions. Then two more sources of Muslim law appeared: ijma - the agreed opinion of authoritative theologians and jurists and qiyas - judgment by analogy.

Soviet historians interpret the social basis of early Islam differently. According to the first concept mentioned above, early Islam reflected the process of decomposition of the primitive communal system and the formation of the slave system in North Arab society. Only later, in connection with the feudalization of Arab society, Islam gradually developed into the religion of feudal society. According to the second concept, Islam from the very beginning was the ideology of early feudal society, although its social essence emerged more clearly later, after the Arab conquests.

The first steps of the Arab state and Arab conquests

After the death of Muhammad in Medina (summer 632), Abu Bekr, a merchant, old friend, father-in-law and associate of Muhammad, was elected caliph (“deputy” of the prophet), as a result of long disputes between the Muhajirs and Ansars. Caliphate power went to Abu Bekr (632-634) at a time when the unification of Arabia was not yet completed. Immediately after the death of Muhammad, many Arab tribes rebelled. Abu Bekr brutally suppressed all these uprisings. After his death, another associate of Muhammad, Omar (634-644), became caliph.

Already under the first caliph, the conquest movement of the Arabs began, which played a huge role in the history of the Mediterranean countries, Western and Central Asia. The international situation was very favorable for the success of the Arab conquests and the spread of Islam. The long war between the two great powers of that time - Byzantium and Iran, which lasted from 602 to 628, exhausted their strength. The Arab conquests were partly facilitated by the long-established weakening of economic ties between Byzantium and its eastern provinces, as well as by the religious policy of Byzantium in its eastern regions (persecution of Monophysites, etc.).

The war with Byzantium and Iran began under Abu Bekr. The “companions of the prophet,” the tribal and Meccan nobility led by the Umayya clan, took an active part in it. For the noble elite of Arabia, an external war of conquest with the prospect of enrichment was also the best way to soften internal contradictions in the country by involving broad layers of Arabian Bedouins in campaigns. By 640, the Arabs had conquered almost all of Palestine and Syria. Many civilians were captured as slaves. But many cities (Antioch, Damascus, etc.) surrendered to the conquerors only on the basis of treaties that guaranteed Christians and Jews freedom of worship and personal freedom, subject to recognition of the power of the Arab-Muslim state and payment of taxes. The subjugated Christians and Jews, and later also the Zoroastrians, formed in the Arab state a special category of a personally free but politically disadvantaged population, the so-called dhimmi. By the end of 642, the Arabs conquered Egypt, occupying the most important port city of Alexandria, in 637 they took and destroyed the capital of Iran, Ctesiphon, and by 651 they completed the conquest of Iran, despite the stubborn resistance of its population.

2. Arab Caliphate in the 7th-10th centuries.

Consequences of the Arab conquests of the 7th-8th centuries.

The vast Arab state formed as a result of the conquests - the Caliphate - was very different from the Arab state in the first years of its existence. Having no experience in managing a complex state apparatus, Arab military leaders were then only interested in seizing land and military booty, as well as receiving tribute from the conquered population. Until the beginning of the 8th century. the conquerors preserved local orders and the former Byzantine and Iranian officials in the captured areas. Therefore, initially all paperwork was conducted in Syria and Palestine in Greek, in Egypt - in Greek and Coptic, and in Iran and Iraq - in Middle Persian. Until the end of the 7th century. In the former Byzantine provinces, Byzantine gold dinars continued to be in circulation, and in Iran and Iraq - silver Sasanian dirhams. The caliph united in his hands secular (emirate) and spiritual (imamate) power. Islam spread gradually. The caliphs provided various benefits to converts, but until the middle of the 9th century. in the Caliphate, widespread religious tolerance towards Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians was maintained.

The Arab conquest of the Byzantine regions and Iran was accompanied by a redistribution of the land fund. The “lands of the Khosroes,” that is, the Sasanian kings, and the lands of the Iranian farmers killed in battles passed to the conquerors. But some Iranian and Byzantine landowners who submitted to the Arabs retained their possessions. The largest part of the land in Iraq, Syria and Egypt was declared state property, and the peasants living on these lands became hereditary tenants subject to land taxes. The remaining lands were gradually appropriated by the Arab nobility. Thus, the family of Ali - Muhammad's son-in-law - received the estates of the Sasanian kings in Iraq. The sons of the caliphs Abu Bekr and Omar also became the largest landowners in Iraq, and the Meccan Umayyads received huge possessions in Syria.

On the appropriated lands, Arab landowners preserved the system of feudal exploitation of local peasants that already existed before the arrival of the Arabs. But many “companions of the prophet,” having become landowners, exploited thousands of captive slaves captured during the wars both in agriculture and in crafts. Very interesting data in this regard is provided by the Arab authors Ibn Sad, Yakubi, Ibn Asakir, Ibn al-Asir and others. Thus, they report that the “companion of the prophet” Abd-ar-Rahman ibn Auf owned 30 thousand slaves; Muawiyah ibn Abu Sufyan, later the caliph, exploited 4 thousand slaves in his fields and gardens in Hijaz alone; the governor of Basra, Mughira ibn Shuba, demanded 2 dirhams daily from his artisan slaves settled in Medina and other places. One of Mugira's slaves, the Christian Persian Abu Lulua, a carpenter and stonemason by trade, once brought a complaint to Caliph Omar about his master and his unbearable demands. Omar did nothing to help Abu Lulua and he, driven to despair, the next day killed the caliph in the mosque with a dagger (in 644). The death of Caliph Omar at the hands of a captive slave is a clear indication of the contradictions that existed between slaves and slave owners in the Arab Caliphate.

Thus, slave relations in the Caliphate of the 7th-8th centuries. were still very strong, and the process of further feudal development of this society unfolded at a slow pace. This was also explained by the fact that in the early feudal society of the former Byzantine and Sasanian provinces, the slave system was preserved until the Arab conquest. The Arab conquest, accompanied by the transformation of many captives into slaves, extended the existence of this way of life in feudal society.

During the conquest, a significant number of Arabs moved to new lands. At the same time, some of the Arabs subsequently switched to sedentary life, while other Arabs continued to lead a nomadic lifestyle in new places. In the conquered areas, the Arabs founded military camps, which then turned into cities: Fustat in Egypt, Ramla in Palestine, Kufa and Basra in Iraq, Shiraz in Iran. The Arabization of Iraq and Syria, where the main population - the Syrians (Arameans) - spoke a language related to Arabic of the Semitic system and where there was a significant Arab population even before the conquest, proceeded quickly. The Arabization of Egypt and North Africa was much slower, and the countries of Transcaucasia, Iran and Central Asia were never Arabized. On the contrary, the Arabs who settled in these countries later assimilated with the local population and adopted their culture.

Caliphate in the 7th and first half of the 8th century.

During the reign of the first two caliphs - Abu Bekr and Omar - there was still a desire to maintain the fiction of equality of all Muslims, which was so sought by the lower classes of Arab society - ordinary nomads, farmers and artisans. These caliphs tried in their private lives not to stand out from the mass of Arabs. Abu Bekr and Omar also tried to adhere to the Koranic sura on military spoils, according to which each warrior was supposed to receive his share of the spoils during the division. However, already the reign of the third caliph, Osman (644-656), who came from the wealthy Meccan family of Omeya, was clearly aristocratic in nature. Osman transferred all the highest civil power into the hands of his relatives and their henchmen, and military power into the hands of the tribal leaders associated with them. Under him, the seizure of vast lands in Syria, Egypt and other conquered countries was encouraged in every possible way.

The growth of social inequality caused strong discontent among the masses of Arab society. Another Arab poet said to Caliph Omar: “We take part in the same campaigns and return from them; Why do they (i.e., the nobility) live in abundance, while we remain in poverty?” Othman’s policies led to uprisings of the Arabian Bedouins and farmers. The discontent of the people was used for their own purposes by supporters of Ali (Muhammad’s son-in-law), the so-called Shiites (from the Arabic word “shia”, which means “group”, “party”), representing another part of the nobility, hostile to Ottoman. The Shiites had especially many supporters in Iraq. Shiism, which initially represented only a political movement, later turned into a special direction in Islam. One of the main provisions of Shiism stated that the legitimate head, spiritual (imam) and political (emir), of the Muslim community can only be the son-in-law of the prophet - Ali, and after him - Alida, i.e. the descendants of him and Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad.

Three groups of dissatisfied people - from Kufa, Basra and Egypt - arrived in Medina under the guise of pilgrims and, uniting with the Medinians, demanded that Osman change the governors he had appointed. Osman promised to satisfy their demands. However, Umayyad Marwan, Osman's nephew and de facto ruler of the Caliphate, wrote a secret order to capture the rebel leaders. But this letter was intercepted by the rebels. They besieged the caliph's house and killed him (656).

Ali (656-661) was elected as the fourth caliph, but the Quraish nobility could not come to terms with the loss of power. The governor of Syria, Muawiyah ibn Abu Sufyan from the Umayya clan, did not recognize Ali and began a war with him. Ali, supported not only by the masses of Arabia who opposed the Quraish, but also by the Arab nobility from Iraq, was afraid of the masses and was ready to compromise with Muawiya. This policy of Ali caused discontent and division in his camp. A large number of his former supporters left him, receiving the name Kharijites (“gone”, rebels). The Kharijites put forward the slogan of a return to “original Islam,” by which they understood a system of social equality for all Muslims, with the transfer of lands into the common ownership of the Muslim community and equal division of military spoils. The Kharijites demanded the election of a caliph by all Muslims, and not just by the “companions of the prophet.” Subsequently, the Kharijites turned into a special religious sect.

In 661 Ali was killed in Kufa by a Kharijite. Ali-Muawiya's rival turned out to be the winner. The Arab nobility of Syria and Egypt proclaimed him caliph. The transfer of power to the Umayyad dynasty (661-750) meant a complete and open political victory of the Arab nobility over the masses of the Arab tribes. Muawiyah I moved the capital to Damascus, well aware of the enormous role Syria with its rich port cities could play in economic and political relations. Syria really became a convenient springboard for further Arab conquests in the Mediterranean countries, raids on Byzantine Asia Minor and the countries of Transcaucasia.

Having achieved power, the Umayyads sought to rely not on the entire Arab nobility, but on a relatively narrow group of their supporters. The Caliph's court in Damascus and its followers in Syria were placed in the most privileged position. Therefore, in other parts of the Caliphate, not only the masses of the people, but also the local landowners were dissatisfied with the Umayyads. In Arabia, discontent was expressed by the broadest sections of the Bedouin, as well as by such groups of Arab nobility as the “companions” of Muhammad and their relatives in Mecca and Medina, who had previously played a prominent political role, but were now removed from power.

In the year of the death of Mu'awiyah I (680), the Shiites attempted to rebel against the Umayyads in Iraq, but at Karbala, the detachment of the pretender to power, Imam Hussein, the son of Ali, was defeated, and Hussein himself was killed. At the same time, a new uprising took place in Arabia (680-692), where the son of Zubeir, one of the main associates of Muhammad, who was also recognized as caliph by the rebels in Iraq, was proclaimed caliph. Both the popular masses of Arabia and the Medinan and Meccan nobility took part in this uprising. The commander of the Umayyad caliph Abd-al Melik (685-705) Hajjaj only with difficulty managed to suppress the uprising and take Mecca in 692. He was in 697. with terrible cruelty suppressed the uprising of the Kharijites in Iraq, who declared that since the Umayyads had betrayed “original Islam,” a “war for faith” must be waged against them. The Kharijites united the broad masses of peasants and Bedouins under their banner.

Agrarian relations under the Umayyads. The situation of the peasants

The largest part of the land fund and irrigation structures in the main areas of the Caliphate was the property of the state. A smaller part of the land fund consisted of lands of the caliph's family (sawafi) and lands that were privately owned. These lands (mulk) were bought and sold. The institution of mulk, corresponding to the Western allod, was legally recognized under Caliph Mu'awiya I. Under the Umayyads, insufficiently developed forms of feudal property dominated - in the form of state and mulk lands. But during this dynasty, the beginnings of conditional feudal land ownership also appeared: plots of land (katia) given to military people for service, and larger territories (khima) transferred to Arab tribes, both nomadic and agricultural.

The land was cultivated mainly by peasants subjected to feudal exploitation, although some Arab landowners continued to combine feudal exploitation of peasants with exploitation of slave labor. On state lands, slave labor is also used when digging and periodically cleaning canals and canals. The size of land taxes (kharaj) increased sharply under the Umayyads. Part of the funds collected from state lands went in the form of salaries to military officials and in the form of pensions and subsidies to members of the families of the “prophet” and his “companions.”

The situation of peasants on state lands and on the lands of individual feudal lords was extremely difficult. Arab authorities back in the 7th century. introduced the practice of making it mandatory for peasants to wear lead tags (“seals”) around their necks. The place of residence of the peasant was recorded on these tags so that he could not leave and evade paying taxes. Kharaj was collected either in kind, in the form of a share of the harvest, or in money, in the form of constant payments from a certain land area, regardless of the size of the harvest. The last type of kharaj was especially hated by the peasants. How difficult the Kharaj was for the masses can be seen in the example of Iraq. This rich region with many cities, with developed commodity production, transit caravan routes and an extensive irrigation network under the Sassanids (in the 6th century) generated annually up to 214 million dirhams in taxes. The conquerors raised taxes so much that it caused the decline of agriculture in Iraq and the impoverishment of the peasants. The total amount of taxes at the beginning of the 8th century. compared to the 6th century. decreased threefold (to 70 million), although the amount of taxes increased.

The revolt of Abu Muslim and the fall of Umayyad power

The Umayyads continued the policy of great conquests and constant predatory raids on neighboring countries by land and sea, for which a fleet was built in the Syrian ports under Muawiya. By the beginning of the 8th century. Arab troops completed the conquest of North Africa, where resistance was provided not so much by Byzantine troops as by warlike and freedom-loving nomadic Berber tribes. The country was greatly devastated. In 711-714. The Arabs conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula, and by 715 they had largely completed the conquest of Transcaucasia and Central Asia.

The dissatisfaction of the broad masses of the people in the conquered countries with the Umayyad policies was enormous. All that was needed was a reason for a widespread movement to begin. The dissatisfied were led by followers of the Shiites and Kharijites, and in the 20s of the 8th century. Another political group appeared, which received the name Abbasid, since it was led by the Abbasids, wealthy landowners in Iraq, descendants of Abbas, Muhammad's uncle. This group sought to exploit the discontent of the broad masses in order to seize power. The Abbasids laid claim to the caliphal throne, pointing out that the Umayyads not only were not relatives of the prophet, but were also descendants of Abu Sufyan, Muhammad's worst enemy.

Most of the dissatisfied people were in the east of the Caliphate, in the Merv oasis. The preparations for the uprising here were led by a certain Abu Muslim, a Persian by origin, a former slave, who saw a strong ally in the Abbasids and their supporters. But the goals of Abu Muslim and the Abbasids coincided only at the first stage. Acting on their behalf, Abu Muslim sought to destroy the Umayyad Caliphate, but at the same time to alleviate the plight of the people. Abu Muslim's preaching was an exceptional success. Arab sources colorfully describe how peasants moved from the villages and cities of Khorasan and Maverannahr (i.e. “Zarechye.” The Arabs called the lands between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya) to designated places on foot, on small poxes, and sometimes on on horseback, armed with whatever they could. In one day, peasants from 60 villages near Merv rose up. Artisans and merchants also came to Abu Muslim; many local Iranian landowners (dekhkans) also sympathized with his fight against the Umayyads. The movement under the black banner of the Abbasids temporarily united people of different social classes and different nationalities.

The uprising began in 747. After a three-year struggle, the Umayyad troops were finally defeated. The last Umayyad caliph, Merwan II, fled to Egypt and died there. Abbasid Abu-l-Abbas, who committed a massacre of members of the Umayyad house and their supporters, was proclaimed caliph. The power of the Abbasids was not recognized by the Arabs on the Iberian Peninsula, where a special emirate was formed. Abbasids (750-1258) ( The Caliphate as a state collapsed by 945, after which the Abbasid caliphs retained only spiritual power in their hands; around 1132 the Abbasids regained political power, but only within Lower Iraq and Khuzistan.), having seized power in the Caliphate, deceived the expectations of the broad masses. Peasants and artisans did not receive any relief from the tax burden. Seeing in Abu Muslim a possible leader of a popular uprising that could break out at any moment, the second Abbasid caliph, Mansur (754-775), ordered his death. The murder of Abu Muslim (in 755) served as an impetus for the protests of the masses against the power of the Abbasids.

The Abbasids could not remain in Damascus, since there were too many Umayyad supporters in Syria. Caliph Mansur founded a new capital - Baghdad (762) near the ruins of Ctesiphon and began to allow Iranian farmers to govern along with representatives of the Arab aristocracy.

Development of feudal relations in the Caliphate in the middle of the 8th and 9th centuries. Popular movements

Under the Abbasids, most countries of the Caliphate continued to be dominated by feudal state ownership of land and water. At the same time, a form of conditional feudal land ownership quickly began to develop - an act (in Arabic - “allotment”), which was given to service people for life or temporary holding. Initially, iqta meant only the right to rent from land, then it turned into the right to dispose of this land, reaching its greatest distribution from the beginning of the 10th century. Land holdings of Muslim religious institutions - inalienable waqfs - also arose in the Caliphate.

On the basis of taxation, the entire territory was divided into lands taxed by kharaj (they mainly belonged to the state), lands taxed in the morning, i.e. “tithe” (most often these were mulk lands), and lands exempt from taxation (including included waqf lands, lands of the caliph family and iqta). The rent from the latter went entirely to the benefit of the landowners.

The entire second half of the 8th century. and the first half of the 9th century. passed in the Caliphate under the sign of the struggle of the people and, above all, the peasant masses against the power of the Abbasids. Among the uprisings against the Abbasid Caliphate, it is necessary to note the popular movement led by Sumbad in Khurasan in 755, which spread to Hamadan. The movement of the popular masses against the Abbasids unfolded with enormous force in 776-783. in Central Asia (Mukanna uprising). Almost simultaneously (in 778-779) a large peasant movement arose in Gurgan. Its participants were known as surkh alem - “red banners”. This is perhaps the first use in history of the red banner as an emblem of the people’s uprising against their oppressors. In 816-837 A large peasant war broke out under the leadership of Babek in Azerbaijan and Western Iran. In 839, in Tabaristan (Mazandaran) there was an uprising of the masses under the leadership of Mazyar. It was accompanied by the extermination of Arab landowners and the seizure of their lands by peasants.

The ideological shell of peasant uprisings in Iran, Azerbaijan and Central Asia in the 8th-9th centuries. was most often the teaching of the Khurramite sect ( The origin of this name is unclear.), which developed from the Mazdakite sect. The Khurramites were dualists; they recognized the existence of two constantly fighting world principles - light and darkness, otherwise - good and evil, God and the devil. The Khurramites believed in the continuous incarnation of the deity in people. They considered Adam, Abraham, Moses, Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and after them various Khurramite “prophets” to be such incarnations of deity. A social system based on inequality of property, violence and oppression, in other words, class society, the Khurramites considered the creation of a dark, or devilish, principle in the world. They preached an active struggle against an unjust social system. The Khurramites put forward the slogan of common land ownership, that is, the transfer of all cultivable lands to the ownership of free rural communities. They sought the liberation of the peasantry from feudal dependence, the abolition of state taxes and duties, and the establishment of “universal equality.”

The Khurramites treated Arab domination, “orthodox” Islam and its rituals with implacable hatred. The Khurramite uprisings were movements of peasants who opposed foreign domination and feudal exploitation. Therefore, the Khurramite movements played a progressive role.

Under Caliph Mamun (813-833), there was a powerful uprising of peasants in Egypt, caused by tax oppression. Mamun himself went to Egypt and committed a bloody massacre there. Many Copts ( The descendants of the ancient Egyptians, who made up the indigenous population of Egypt, are Myophysite Christians by religion.) were killed, and their wives and children were sold into slavery, so that the Delta, the most fertile and populated region of Egypt, was then deserted (831).

Popular uprisings, although defeated, did not pass without a trace. Frightened by the scale of the movements, the caliphs were forced to make some changes to the exploitation system. Under Caliph Mahdi (775-785), it was forbidden to impose additional taxes on peasants. Under Caliph Mamun, the highest rate of kharaj collected in kind was reduced from 1/2 to 2/5 of the harvest. At the beginning of the 9th century. The practice of mandatory peasants wearing lead tags around their necks disappeared. The situation of peasants in the eastern regions of the Caliphate in the 9th century. improved, especially after the Caliphate began to disintegrate, and local feudal states began to emerge on its ruins.

Islam as a feudal religion

Since the people's liberation movements in the Caliphate most often unfolded under the ideological shell of religious sectarianism, Mamun's government considered it necessary to establish state confession compulsory for all Muslims. Until then, this had not actually been achieved: Islam represented. A motley combination of different movements and sects (Sunnis, Shiites, Kharijites, etc.). Even “orthodox” (Sunni) Islam, which was the religion of the ruling class, had several theological schools that diverged from each other on ritual details and legal issues.

Sufism, a mystical movement that was influenced by Christian asceticism and Neoplatonism, also became widespread in Islam. His followers taught that a person can, through self-denial, contemplation, ascetic “deeds” and rejection of the “good things of this world,” achieve direct communication and even merging with God. Sufism gave rise to communities of Muslim ascetics (in Arabic - fakirs, in Persian - dervishes), who later, especially between the 10th and 15th centuries, appeared in large numbers in Muslim countries and played a role to a certain extent similar to the role of monks in Christian countries.

Mamun's government declared the state confession, which arose back in the 8th century. the teachings of Muslim rationalist theologians - the Mu'tazilites ("separated"). In the teachings of the Mu'tazilites, four main points stood out: the denial of anthropomorphism (the idea of God in human form) characteristic of early Islam - God is not like his creations and is unknowable to them, the Mu'tazilites argued; The Koran is not eternal, as the Sunnis taught, but created; human will is free and does not depend on the “predestination” of God; The caliph, who is also the imam, is obliged to “affirm the faith” not only with “tongue and hand” (sermon and writings), but also with the sword, in other words, he is obliged to persecute all “heretics.”

Under Caliph Mutawakkil (847-861), Sunnism again became the official religion. In the 10th century there was a separation of Sunni theology from jurisprudence (law). This law reflected new feudal institutions. In the same X century. a system of “new orthodox theology” (kalam) was created, with a much more complex dogma than in early Islam. Like the later Catholic theologians of the West, the followers of Kalam tried to rely not only on the “authority” of the “holy scripture”, but also on the positions of ancient philosophers, primarily Aristotle, distorted by them, although without direct references to them. The founder of kalam was the theologian Ashari (10th century), and kalam received full development at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries. in the writings of Imam Muhammad Ghazali, a Persian.

Ghazali brought kalam closer to Sufism, which early Muslim theologians disapproved of. The clergy, or rather the class of theologians and lawyers, took shape. As in medieval Christianity, the cult of numerous “saints” and their tombs now began to play a large role in Islam. Dervish monasteries received extensive land holdings. Particularly characteristic of Islam of this period was the preaching of humility, patience and contentment with one’s lot addressed to the masses. Starting from the second half of the 9th century. “Orthodox” Islam became increasingly intolerant towards Christians, Jews and especially Muslim “heretics”, as well as representatives of secular science and philosophy.

Iran in the 9th century.

As a reward for the services rendered by the Iranian nobility to Caliph Mamun in the struggle for the throne with his brother Amin, the Caliph was forced to distribute extensive land grants to them. Moreover, Khorasan was turned into a hereditary governorate of the Iranian peasant family of Tahirids (821-873), which provided special services to Mamun. Tahirid Abdallah (828-844) was idealized by eastern feudal historiography, portraying him as a lover of the people. In fact, he was simply an intelligent and far-sighted representative of the feudal class. He tried to accurately record the size of the kharaj and published the “Book of Canals” - a code of water law on the procedure for distributing water for irrigating fields. But when the peasants rebelled, Abdallah resorted to brutal reprisals against them. So he suppressed the peasant uprising in Sistan (831).

Under the second successor of Abdallah-Muhammad (862-873), the Tahirid governor in Tabaristan, through his oppression and seizure of communal lands, brought local peasants to revolt (864). This uprising was used by the Shiite, a descendant of Ali, Hassan ibn Zeid, who became its leader, in order to found an independent Shiite Alid state on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea.

At this time, a state arose in the east of Iran, ruled by the Saffarid dynasty. The founder of this dynasty was Yaqub ibn Lays, nicknamed Saffar (copper worker), who participated in the suppression of the peasant movement that took place in Sistan under the leadership of the Kharijites. After the suppression of this uprising, the mercenary army chose Yaqub as their emir and captured Sistan (861). The troops assembled by Yakub conquered a significant part of what is now Afghanistan (the regions of Herat, Kabul and Ghazna), and then Kerman and Fars. Having defeated the army of the Tahirid emir in Khorasan, Yakub established his power in this area (873). In 876, Yaqub launched a campaign against Baghdad, but his army was defeated in a clash with the army of the Baghdad caliph. After 900, the Saffarid possessions came under the rule of the Samanids, a dynasty that arose around 819 in Transoxiana. The Samanid state lasted until 999.

Collapse of the Caliphate in the 9th century.

An independent state was also formed in Egypt (868). Power here was seized by the Caliph's deputy, Ahmed ibn Tulun, a Central Asian Turk who emerged from the Caliph's guards. The Tulunid dynasty (868-905) subjugated, in addition to Egypt, also Palestine and Syria. Even earlier, a state independent of the Baghdad caliph was formed in Morocco, led by the Idrisid dynasty (788-985). An independent state led by the Aghlabid dynasty (800-909) emerged in Tunisia and Algeria. In the 9th century. local feudal statehood was revived in Central Asia, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Thus, during the 9th century. and in the first half of the 10th century. The Arab Caliphate was experiencing a process of gradual political disintegration. This was facilitated by the different levels of economic development of the countries of the Caliphate, the comparative weakness of economic and ethnic ties between them and the growth of large land ownership of individual feudal lords at the expense of state lands, and therefore the political separatism of local large feudal lords intensified. People's liberation uprisings against his rule played a huge role in the process of the political disintegration of the Caliphate. Although they suffered defeats, they undermined the military power of the Caliphate on the ground.

The desire of large feudal lords for political independence led to the formation of local hereditary emirates, which gradually turned into independent states. Thus, the Tahirids in Iran and the first Samanids in Central Asia, without allowing the central apparatus of the Caliphate to interfere in the management of their lands, still paid tribute to the caliph (part of the kharaj they collected). The Saffarids and the later Samanids, as well as the Aghlabids of North Africa and the Tulunids of Egypt, no longer paid any tribute to the caliph, appropriating the entire amount of the kharaj. Nominally recognizing the power of the caliph, they only retained the minting of the caliph's name on coins and the obligatory prayer for him in mosques.

At the end of Mamun's reign, popular movements against the Abbasids intensified so much that the Caliphate was threatened with complete collapse. By this time, the former Arab tribal militias had lost their importance and were not reliable enough as a support for the dynasty. Therefore, under Mamun, a permanent horse guard was created from elements alien to the population of the Caliphate, namely from young, well-trained slaves (ghulams, otherwise Mamluks) ( In Arabic, “gulam” meant “young man”, “well done”, as well as “slave”, “military servant”; “Mamluk” - “taken into possession”, “slave”.) of Turkic origin, bought by slave traders in the steppes of Eastern Europe and present-day Kazakhstan. This guard soon gained great strength and began to overthrow some caliphs and enthrone others at their own discretion. Since the 60s of the 9th century. the caliphs became puppets in the hands of their own guards.

Development of productive forces in the 9th-10th centuries.

The political disintegration of the Caliphate did not at all mean the economic decline of the countries that were part of it. On the contrary, the transformation of the feudal mode of production into the dominant one, the formation in these countries of local independent feudal states, which partially spent collected taxes on the development of irrigation, as well as some improvement associated with the latter in the position of the peasants - all this stimulated in the 9th-10th centuries. growth of productive forces in the countries of the Mediterranean, Western and Central Asia. General progress in agriculture was expressed not only in large irrigation works and in improved construction of carises, but also in the spread of hydraulic wheels, water drawers, and the construction of dams, reservoirs, locks and river canals; such, for example, are the large canals Sila from the Euphrates River, Nahr Sarsar and Nahr Isa between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, Nahravan from the Tigris River, etc.

Hand mills and mills driven by animal power began to be replaced everywhere by water mills, and in some places by windmills. The large water mill in Baghdad had up to 100 millstones. Long walls were erected to protect oases from sand drift. The cultivation of sugar cane, grapes, flax in the western regions of the Caliphate, and cotton and rice in the eastern regions expanded; Sericulture also developed.

In the IX-X centuries. There was an intensive process of separation of crafts from agriculture and the formation of the feudal city as a center of commodity production. The sources of this time note a great increase in the technology of textile, ceramic, paper and perfume crafts, as well as metal processing. Trade turnover expanded enormously, caravan trade increased, both internal and external: with India, China, with the countries of Eastern Europe, including Russia (from the 9th century), and with the countries of the northern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. In this regard, the credit system, the use of checks and exchange transactions with money changers developed.

Revolt of the Zinj

The strongest blow to the Abbasid Caliphate was dealt by the powerful uprising of the Zinj in the 9th century. The Zinj rebellion was started by slaves, mostly dark-skinned Africans. Slave traders acquired them mainly at the slave market on the island of Zanzibar (in Arabic - al-Zinj). Therefore, these slaves in the Caliphate were called Zinj. The Zinj, united in large groups, were engaged in clearing vast areas of state lands (called mawat - “dead” and lying in the vicinity of Basra in Iraq) from salt marshes in order to make these lands suitable for irrigation and cultivation. How large the number of black and white slaves was in the Caliphate is evident from the fact that, according to the report of the historian Tabari, a contemporary of the Zinj uprising, in only one district of Lower Mesopotamia up to 15 thousand slaves worked on state-owned lands. They all joined the rebels.

The uprising was led by an energetic and educated leader, an Arab by origin, Ali ibn Muhammad al-Barkui, who belonged to the Kharijite sect. The Zinj revolt lasted 14 years (869-883). Not only many tens of thousands of slaves took part in it, but also peasants and Bedouins.

The Zinj captured a significant part of Iraq with the important city of Basra and created their own fortified camp (the city of al-Mukhtara), then they advanced to Khuzistan and took its main city of Ahwaz. The leaders of the Zinj, having appropriated fertile lands, themselves turned into feudal-type landowners. In the estates they seized for themselves, the peasants were not exempt from paying kharaj. Even the institution of slavery was not abolished; only the slaves who participated in the uprising were freed; During raids on Khuzistan and other areas, the Zinj leaders themselves enslaved civilians. The Zinj leaders slavishly copied the state forms of the Caliphate and proclaimed Ali ibn Muhammad caliph. All this led to the abandonment of the movement by peasants and Bedouins who were disillusioned with it. Zinj found themselves isolated, which helped the caliph's troops, who also had a large river fleet, suppress the uprising.

The Zinj uprising, despite a number of its weaknesses, had a progressive significance in the history of the countries of the Caliphate. It led to a decline in the role of slave labor in the economic life of Iraq and Iran. Since the 9th-10th centuries. landowners planted slaves in large numbers on plots of land, essentially turning them into feudal dependent peasants. By the end of the 9th century. These countries developed a developed feudal society.

Ismailis

In the second half of the 8th century. A split occurred among the Shiites. Imam Ja'far, who was the sixth representative of the dynasty of Shiite imams (descendants of Caliph Ali), deprived his eldest son Ismail of the right to inherit the imam's dignity. Perhaps such an important decision of Jafar was caused by the fact that Ismail sided with the extreme Shiites or sympathized with them. The latter openly expressed their dissatisfaction with Jafar's indecisive, compliant policy towards the reigning Sunni Abbasid dynasty. The extreme Shiites declared the decision of the Shiite Imam wrong and recognized Ismail as their legitimate and last Imam. This most active Shia minority began to be called Ismailis, or seven-year-olds, since they recognized only seven imams. The majority of Shiites, who recognize the twelve imams, descendants of Ali, as their supreme spiritual leaders, are called Imamites, or Twelvers.

The Ismailis created a strong secret organization, whose members carried out active preaching. Ismaili preaching had significant success among the working population of cities, and partly among peasants and Bedouins in Iraq and Iran, and then in Central Asia and North Africa. From the end of the 9th century. Under the strong influence of the idealistic philosophy of Neoplatonism, the teaching of the Ismailis took shape, which moved very far away from both the so-called “orthodox” (Sunni) Islam and the moderate Shiism of the Imami. According to the teachings of the Ismailis, God isolated from himself a creative substance - the “World Mind”, which created the world of ideas and, in turn, isolated from himself a lower substance - the “World Soul”, which created matter (planets and Earth). The Ismailis interpreted the Koran allegorically and rejected most of the rituals of Islam.

The Ismailis taught that after certain periods of time the deity is embodied in people: natiq (in Arabic - “speaker”, i.e. “prophet”) is the embodiment of the “World Mind”, and asas (in Arabic - “basis”, “ foundation"), the natik's assistant, who explains his teachings, is the embodiment of the "World Soul". The Ismailis created first 7, then 9 degrees of initiation into the secrets of their sect. Only a very few members of the sect reached the highest degrees, to whom members of the lower degrees had to blindly obey, like instruments devoid of will. The Ismaili sect was bound by iron discipline.

Movement of the Karmatians. Completion of the political disintegration of the Caliphate

No less powerful a blow than the Zinj uprising was dealt to the Abbasid Caliphate at the end of the 9th and 10th centuries. The Qarmatian movement is a broad anti-feudal movement of the poorest Bedouins, peasants and artisans in Syria, Iraq, Bahrain, Yemen and Khorasan. The secret organization of the Qarmatians (the origin of the word “Qarmat” is not clear) developed during the Zinj uprising, possibly in the craft environment. The Karmatians put forward slogans of social equality (which did not, however, apply to slaves) and community of property. The ideological form of the Qarmatian movement was the teaching of the Ismaili sect. The Qarmatians recognized the Ismaili leaders, descendants of Ali and Fatima, as their supreme leaders. The name of the head was never spoken and was unknown to the mass of sectarians. The leader and his entourage sent missionaries (dai) to different areas to preach and prepare uprisings.

The first Qarmatian uprising occurred in 890 near the city of Wasit in Iraq. The leader of the uprising, Hamdan, nicknamed Karmat, created the headquarters of the rebels near Kufa, who pledged to contribute a fifth of their income to the public treasury. The Karmatians tried to introduce an equal distribution of means of consumption and organized fraternal meals. In 894 there was a Qarmatian uprising in Bahrain. In 899, the rebels captured the city of Lahsa and declared it the capital of the newly formed Qarmatian state in Bahrain. It existed for more than a century and a half.

In 900, the Qarmatian Dai Zikraweikh called for an uprising of the Bedouins of the Syrian Desert. The uprising spread across Syria and lower Iraq; in 901 the Qarmatians besieged Damascus. The uprising in Lower Iraq was drowned by the Caliph's troops in a flood of blood in 906, but in some areas of Syria and Palestine the Qarmatians continued to fight throughout the 10th century. From 902 to the 40s of the 10th century. There were Qarmatian uprisings in Khorasan and Central Asia.

The Ismaili poet-traveler Nasir-i Khosrow, who visited Lahsa in the middle of the 11th century, left a description of the social system established in Bahrain by the Qarmatians. The main population of Bahrain, according to this description, consisted of free farmers and artisans. None of them paid any taxes. The city of Lakhsa was surrounded by date groves and arable lands. The state was headed by a board of six rulers and six of their assistants (yezirs). The state owned 30 thousand black and Ethiopian purchased slaves, whom it provided to farmers for work in the fields and gardens. This was an attempt to revive the communal slavery characteristic of the first centuries of our era. Interest-free loans were issued from the public treasury to needy farmers and artisans. There were 20 thousand people in the militia. The Qarmatians of Bahrain did not have mosques, did not perform statutory prayers, did not fast, and treated with complete tolerance the followers of all religions and sects who settled among them.

By the middle of the 10th century. The political disintegration of the Caliphate, weakened as a result of the growth of feudal fragmentation, the liberation struggle of the countries of Western and Central Asia and the uprisings of the exploited masses, ended. The Bund dynasty (from 935), which arose in Western Iran, captured Iraq along with Baghdad in 945, depriving the Abbasid caliphs of secular (political) power and retaining only spiritual power for them. The Bunds took away most of his family estates from the Abbasid caliph, leaving him, as an ordinary feudal landowner, one estate with the rights of iqta and allowing him to keep only one scribe to manage it.

Arab culture

Orientalists of the 19th century, who did not have all the now known sources and were influenced by the medieval Muslim historical tradition, believed that throughout the Middle Ages, in all countries that were part of the Caliphate and adopted Islam, a single “Arab” or “Muslim” dominated. culture. The external justification for such a statement was that classical Arabic had long dominated in all these countries as the language of government, religion and literature. The role of the Arabic language in the Middle Ages was indeed exceptionally great. It was similar to the role of the Latin language in medieval Western Europe. However, in countries with a non-Arab population that became part of the Caliphate, local cultures continued to develop, which only came into interaction with the culture of the Arabs and other peoples of Western and Central Asia and North Africa. Arab medieval culture, in the strict sense of the word, should be called only the culture of Arabia and those countries that underwent Arabization and in which the Arab nation developed (Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, North Africa). It is the culture of these countries that is discussed below.

Having assimilated and processed a significant part of the cultural heritage of the Persians, Syrians (Arameans), Copts, the peoples of Central Asia, the Jews, as well as the heritage of Hellenistic-Roman culture, the Arabs themselves achieved great success in the field of fiction, philology, history, geography, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, logic and philosophy, as well as in the field of architecture, ornamental art and artistic craft. The Arabs' assimilation of the heritage of ancient culture was one-sided due to the influence of Islam: they willingly translated works on the exact sciences and philosophy from Greek (or from Syriac translations from it), but almost all of the extensive Greek and Latin poetry, fiction and historical literature were abandoned without attention. The religious prohibition of Islam to depict people and animals (for fear of “idolatry”) eventually killed sculpture and had a detrimental effect on the development of painting.

The greatest flourishing of Arab culture occurred in the 8th-11th centuries. In the VIII - X centuries. works of pre-Islamic Arabic oral poetry of the 6th-7th centuries were recorded (from the words of the rhapsodists) and edited. Abu Tammam and his student al-Bukhturi compiled and edited in the middle of the 9th century. two collections of “Hamas” (“Songs of Valor”), containing works of over 500 Old Arabic poets. Many samples of Old Arabic poetry were included in the huge anthology “Kitab al-aghani” (“Book of Songs”) by Abu l-Faraj of Isfahan (10th century). On the basis of Old Arabic poetry, as well as the Koran, the classical literary Arabic language of the Middle Ages developed. Rich Arabic written poetry of the second half of the 7th and 8th centuries. largely continued the traditions of pre-Islamic oral poetry, maintaining its secular character, imbued with a cheerful mood. Among the poets of the late 7th - early 8th centuries, who sang military exploits, love, fun and wine, Farazdak, the satirist Jarir and Akhtal stood out, all three were panegyrists of the Umayyads.

The heyday of Arabic poetry dates back to the 8th-11th centuries. Feudal-court and urban poetry retained its secular character. Its most prominent representatives are the freethinker Abu Nuwas (756 - about 810), known as the author of love poems and clearly hostile to the ideology of Islam, who wrote that he would like to become a dog that, sitting at the gates of Mecca, would bite every pilgrim who came there, as well as Abu -l-Atahiya (VIII - early IX century), master potter, denouncer of the licentiousness that reigned at the court of Caliph Harun ar-Rashid. No less famous are the poet-warrior Abu Firas (10th century) with his elegy, written in captivity by the Byzantines and addressed to his mother, and Mutanabbi (10th century), the son of a water-carrier, the most brilliant of the Arab poets of this time, a master of exquisite verse.

In the first half of the 11th century. In Syria, the great poet, the blind Abu-l-Ala Maarri, “a philosopher among poets and a poet among philosophers,” worked. His poetry is imbued with a pessimistic condemnation of the morality and social relations of feudal society, as well as feudal strife. He denied the dogma of divine revelation and castigated people who profited from all sorts of superstitions of the masses. Abu-l-Ala called himself a monotheist, but his god is only an impersonal idea of fate. The main rules of morality of Abu-l-Ala are: fighting evil, following your conscience and reason, limiting desires, condemning the killing of any living creature. Between the X and XV centuries. Gradually, a widely popular collection of folk tales, “One Thousand and One Nights,” was formed, the basis for which was a reworking of the Persian collection “A Thousand Tales,” which over time was overgrown with Indian, Greek and other legends, the plots of which were reworked, and the action was transferred to the Arab court and city Wednesday. From the middle of the 8th century. Many translations of literary prose from Syriac, Middle Persian and Sanskrit appeared.

Religious and palace buildings predominated among the architectural monuments. Arab mosques during the Caliphate most often consisted of a square or rectangular courtyard, surrounded by a gallery with arches, adjacent to which was a columned prayer hall. This is how the Amra mosque in Fustat (7th century) and the cathedral mosque in Kufa (7th century) were built. Later they began to be given domes and minarets. Some early mosques in Syria were imitations of the Christian (early Byzantine) domed basilica. These are the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem at the end of the 7th century. and the Umayyad mosque in Damascus at the beginning of the 8th century. A special place in architecture is occupied by the church built under Caliph Abd al-Melik at the end of the 7th century. on the site of what was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD. e. Jewish Solomon's Temple; Muslim mosque Qubbat al-Sakhra (“Dome of the Rock”) in the shape of an octagon, with a dome on columns and arches, magnificently decorated with multi-colored marble and mosaics.

Of the secular buildings, the majestic ruins of the Mshatta castle in Jordan (VII-VIII centuries) and the Umayyad castle of Qusair-Amra from the beginning of the 8th century have been preserved. with highly artistic painting made by Byzantine and Syrian masters and still following the ancient Byzantine traditions. Of the later buildings, it is necessary to note the large minaret in Samarra (IX century), the mosque of Ibn Tulun (IX century) and al-Azhar (X century) in Fustat. Since the 10th century. buildings began to be decorated with arabesques - the finest ornaments, floral and geometric, with the inclusion of stylized inscriptions.

Arab philosophy, initially associated with theological scholasticism (its centers were Kufa and Basra), began to free itself from the influence of the latter after the middle of the 8th century. Arabic translations of the works of Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, as well as a number of mathematicians and physicians of antiquity appeared. This translation activity, in which Syrian Christians played a prominent role, since the time of Caliph Mamun was concentrated in Baghdad in a special scientific institution “Beit al-Hikmah” (“House of Wisdom”), which had a library and an observatory.

If rationalist theologians (Mu'tazilites) and Sufi mystics tried to adapt ancient philosophy to Islam, then other philosophers developed the materialistic tendencies of Aristotelianism. The greatest Arab philosopher al-Kindi (9th century) created an eclectic system in which he combined the opinions of Plato and Aristotle. Al-Kindi's main work is devoted to optics. At the end of the 9th century. A circle of rationalist-minded scientists in Basra, close to the Qarmatians, “Ikhwan al-Safa” (“Brothers of Purity”) compiled an encyclopedia of philosophical and scientific achievements of their time in the form of 52 “letters” (treatises).